For quite some time, Middlegame has argued that promotional price cuts are only an additional attribute for the product during those six or seven seconds that the average shopper surveys the category and makes a choice. It was probably far from controversial when we described these and other merchandising conditions as “temporary” attributes in alignment with predominant TPR (temporary price reduction) terminology. However, price reductions and merchandising conditions continue to use advanced analytics that primarily ignore that these temporary product attributes should probably be evaluated side-by-side with the permanent product attributes.

Conjoint studies are definitely an exception, so I want to point out that this isn’t merely another CIA® platform commercial. What the conjoint suppliers as well as Middlegame are doing received another dose of support from recent work by Pedro Gardete, Stanford Graduate School of Business, and his colleagues in Chile. A quick write-up of their work can be found at The Lingering Impact of Promotional Price Cuts. To me, this is a big deal hidden in plain sight.

Like Middlegame, Professor Gardete worked with scanner data to investigate the impact of promotional price cuts. However, by working directly in partnership with a large Chilean supermarket retailer, his study could offer a true field experiment with all the proper elements of test and control. The experiment manipulated hundreds of the prices normally seen in the 17 large categories (beer, candy, cheese, milk, water, yogurt, etc.) for ten weeks. This passive observation resulted in more than 200,000 shoppers offering their purchase patterns for analysis.

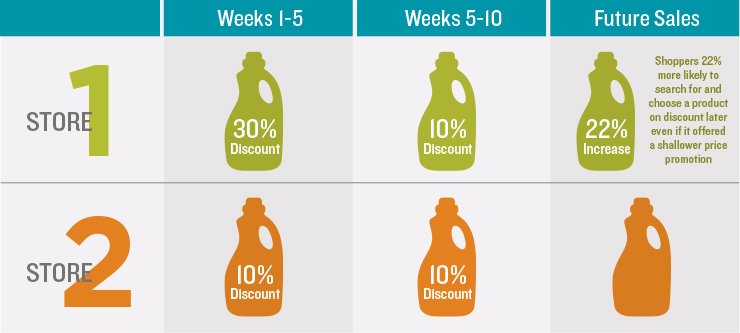

The test selected a series of stores to offer fairly deep discounts of up to 30 percent for a series of specific products during the first 5 weeks. During the same timeframe, a series of control stores offered these products at a shallower 10 percent discount. In the last five weeks, all of the stores offered the same products with a 10 percent discount. After reviewing the full experiment, the data demonstrated that shoppers who received the deep discounts first were 22 percent more likely to search for and choose a product on discount later even if it offered a shallower price promotion.

Professor Gardete suggests that “if you give consumers a big promotion, they become more responsive to any degree of promotion in the future” when summarizing the findings. This sounds a lot like how we talk about loyalty to temporary attributes like price reductions or merchandising, regardless of the permanent attributes of brand, size percent package types that dominate most marketing conversations. Gardette hit this home in the interview as he explains that the marketing tailwind of discounting doesn’t just produce trial and subsequent repeat for your products. These temporary attributes create a loyalty all their own that is easily imitated by competitors.

Everybody gets it. Trade promotions are great for shoppers and help maintain market share for retailers, but have destroyed the profitability of manufacturers. However, you need to continue to “feed the beast,” according to most of our clients. Otherwise, you become irrelevant to shoppers on these temporary attributes and potentially delisted by retailers. While I understand that logic, the real question that Middlegame tries to address is whether to discount at all. When we do discount, what products are going to best use those temporary attributes to maximize incrementality and minimize transferred demand within the portfolio? Can we then create the win-win that is the most profitable for both the retailer and our organization?

Middlegame is the only ROMI consultancy of its kind that offers a holistic view of the implications of resource allocation and investment in the marketplace. Our approach to scenario-planning differs from other marketing analytics providers by addressing the anticipated outcome for every SKU (your portfolio and your competitors’) in every channel. Similar to the pieces in chess, each stakeholder can now evaluate the trade-offs of potential choices and collectively apply them to create win-win results.